A ‘Theory of Change’ is exactly what the term says: it is your theory about the change your project is going to create. The useful thing about a Theory of Change is that, instead of prioritising what you want to do, it makes you think about why.

Ask yourself:

What is your big picture goal - your mission, the legacy you want to leave on this planet?

What is known about how to reach that goal?

What can you do, that no one else can, to help reach that goal?

A Theory of Change has four components, and you should go from right to left.

Check your assumptions

The arrows in a Theory of Change are possibly the most important part of the whole thinking process. The arrows from an activity to an outcome, from an outcome to an impact and so on, are the CAUSAL ASSUMPTIONS you are making. You are saying if I do x, then y will follow.

But will it? What are you basing this assumption on? Are you basing it on prior research? Check your assumptions. Unpack them. See if they hold up under scrutiny.

Things to keep in mind about a Theory of Change

Develop your theory of change WITH the people you are hoping to benefit through the project. Who do you want to experience the desired impacts? Do they want to experience these impacts? Do the desired impacts vary between groups? See my diversity evaluation resources for more information on ensuring you are actually achieving what you say you want to achieve.

Define the goals first, then work backwards

Not everything in the Theory of Change has to be measurable. You can choose the most important things to measure. But what you measure should include the key assumptions which might underpin some of your cause-effect thinking

Activity = What will achieve our goal + What can we do that no one else can.

I have my Theory of Change. Now what?

A Theory of Change is not an evaluation framework. Once you have your Theory of Change, you can use it to help you decide what impacts (and their underlying assumptions) are most important.

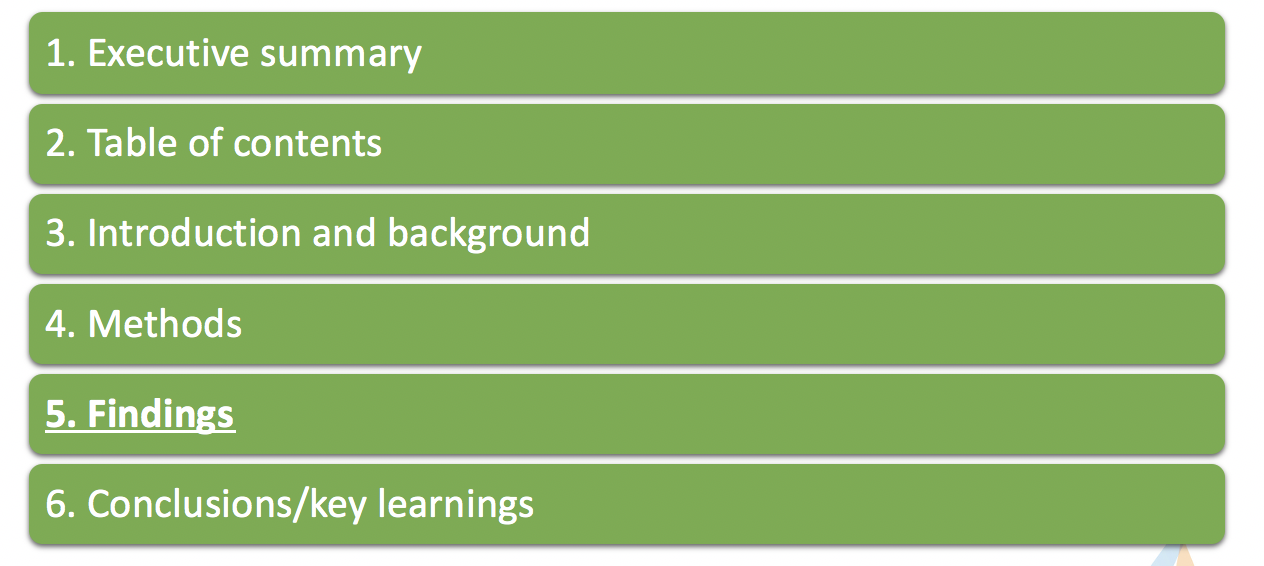

Then you build yourself an Evaluation Framework. Mine normally have three key bits.

Elements of an Evaluation Framework

This site has detailed steps and examples of each of these three elements of an evaluation framework, and a template for an evaluation framework. Enjoy!